The UK government tells a confident story about Britain’s tech business acumen. In one 2023 example, a press release from Rishi Sunak invited investment in the tech sector, calling the UK an ‘island of innovation’. In it, he explained that the UK corporation tax rate was the lowest in the G7 and that the UK capital allowance for investors was ‘one of the most generous’ in the OECD. Even better, the UK Treasury offered ‘full-expensing for qualifying business investments in more plant and machinery for three years – a tax cut worth £27 billion’. This is generous, and notably so when in 2023 the UK spent more than £100 billion servicing the interest on state debts. And, viewed in a certain light, the generosity has got results. The PM also claimed that the UK has created 134 ‘tech unicorns’ – companies with a valuation of more than $1 billion.

For all the hype, it is notable that the FTSE 100 had more domestic tech firms in the year of its founding, 1984, than it has today

Sunak’s wide-eyed enthusiasm is broadly shared by tech boosterists in the UK. A 2021 report by UK start-up cheerleaders Tech Nation also boasted that Britain has launched more than 100 ‘unicorns’. Even if nearly half of those were created between 1990 and the 2008 crash, the figures sound impressive – outstripping every country in the world save China and the US. And Tech Nation claimed better news: ‘The UK now has an incredible 132 futurecorns [companies likely to be worth $1 billion], more than France and Germany combined, which demonstrates the extent to which the UK is leading Europe.’

But a focus on these numbers can be misleading, because Britain’s new businesses do not tend to scale up to become global challengers. The country offers no rivals to the biggest US firms: Meta/Facebook, Apple, Microsoft, Amazon and Alphabet/ Google (MAMAA). To the Forbes list of the biggest 100 publicly traded companies, Britain contributes just three – fewer than Switzerland, Germany, France, Canada, Japan, China or, of course, the US, which can claim 39 of the top 100. And, tellingly, all three UK entrants – GSK, HSBC and Unilever – have their origins not in the dot-com boom, or even in the post-war period, but in the nineteenth century.

For all the hype, it is notable that the FTSE 100 had more domestic tech firms in the year of its founding, 1984, than it has today. The story of one of them, Standard Telephones and Cables (STC), is revealing.

In 1984, STC employed 51,000 people, mostly in the UK, providing telephony services that included deep-sea Atlantic cabling and, through a subsidiary, mainframe computing across UK government departments. In the decades before, STC invented and patented technology to allow fibre-optic cables to transfer data at the speed of light over any distance. And these innovations, developed in STC’s optics lab in Harlow in the 1960s, made the cost of global communication negligible and, decades later, helped enable the World Wide Web.

Yet, like 68 of the original FTSE 100 companies, STC is no longer British-owned. In 1991, it was sold to the Canadian telecoms giant Nortel. And, in the same year in which former STC lab manager Charles Kao received the Nobel Prize in recognition of his fibre-optic work for STC, Nortel filed for bankruptcy. The end came in 2011, when a consortium led by Apple and Microsoft outbid Google to pay $4.5 billion for Nortel’s patents and the residual IP.

Over the decades, other tech firms have fallen in and out of the FTSE 100 index. While some offered innovations that really could have reshaped modern communication, they did not make it. They could not grow. They did not scale.

Consider the UK computing firm Psion. It evolved the first effective pocket computers several years before Apple developed the Newton and Microsoft developed Windows for handheld devices. Today, the Psion Organiser is seen as a forerunner to the smartphone, and its technology certainly foreshadowed it. For example, the low-power operating system developed by the firm was the core of 250 million mobile devices by 2009 before ultimately losing market share to Google’s superior Android platform and Apple’s IOS. Psion entered the FTSE 100 in March 2000 before dropping out after just two months. In 2012, it was purchased by Motorola Solutions of Chicago, Illinois. By 2023 the FTSE 100 contained just three tech firms: Sage, Rightmove and Auto Trader, although arguably only the first of these is really a tech company.

If the UK government is embracing entrepreneurial tech investment, is anything changing? Not really. Even Tech Nation has noticed that one pound in three offered to UK tech firms by institutional investors is American. As for the ‘unicorns’ and the ‘futurecorns’, US investors also dominate larger investment rounds. All of which is a little awkward for Tech Nation itself, which has received some £29 million in sponsorship from the UK government to help boost a start-up culture. As a result, its 2021 report seemed distinctly hedged about the consequence of all this US investment, observing: ‘On the one hand, this could be seen as a sign of strength and burgeoning international reputation for investment returns in UK tech, but on the other, this may be seen as potentially problematic if UK tech firms with significant profit and influence are owned by non-UK actors.’

It seems unthinkable that any of the UK firms backed by US institutional investors will grow to a size that could challenge already dominant US businesses. Sometimes, they are simply bought out by the US giants to take the innovation out of the hands of competitors. In recent years, Google has snapped up the UK companies Dataform and Redux and, perhaps most controversially, the AI innovator DeepMind, bought in 2014.

As UK investor and SongKick co-founder Ian Hogarth has written, the talent pool for serious AI development is small. In 2018 he estimated that there are perhaps 700 people who can contribute to the leading edge of research. ‘I find it hard to believe,’ he wrote, ‘that the UK would not be better off were DeepMind still an independent company. How much would Google sell DeepMind for today? $5 billion? $10 billion? $50 billion? It’s hard to imagine Google selling DeepMind to Amazon, or Tencent or Facebook at almost any price.’

Google paid just £400 million, with no questions asked by the UK government.

Britain’s groundbreaking semiconductor innovations have also drifted away from our shores over the years. Hermann Hauser of Amadeus Capital is an Austrian-born tech investor who is used to making money from selling UK tech firms. Some of Amadeus Capital’s biggest deals have been with US firms such as Microsoft. And, in 2011, Hauser sold UK semiconductor innovator Icera to the US chip-maker Nvidia for $367 million. The sale was designed to help Nvidia engage with the smartphone revolution, but four years later it closed the UK firm with the loss of 300 jobs in Bristol.

Today, Hauser’s view is that Britain’s tech firms suffer not from a lack of ideas, talent or research capacity but because they cannot scale up effectively: ‘Europe actually doesn’t have a startup problem. We produce more startups than the US. It’s not a startup problem, but we have a scale-up problem.’

There is, however, one exception: Arm Holdings. Growing out of the innovative but unsuccessful Acorn Computers in the 1980s, Arm developed chips and software that allowed computer processors to run far faster and with less power than many rivals. Starting in a barn in Cambridge and backed by an investment of £1.5 million from Apple, Arm has grown into one of the most important tech companies in the world. With technology in more than 200 billion devices, the firm has successfully pioneered a business model in which it licenses cutting-edge computer architecture to developers across the globe. The UK company has been so successful for so long that its profits even kept Apple afloat when the US titan sold its modest investment in Arm for $800 million back in the early 1990s.

Hauser saw it all because as well as running Amadeus Capital, he also helped to found Acorn Computers and Arm itself. And it is notable that, in 2020, he led a campaign to persuade UK and EU authorities to intervene to stop Arm being sold to Nvidia in the US by its Japanese owners SoftBank. In a letter to the Financial Times he warned that the sale to a US firm would allow that nation to decide who gets to keep Arm’s innovations or, as he said, it would mean ‘that the American President can decide which companies Arm is allowed to sell to worldwide’.

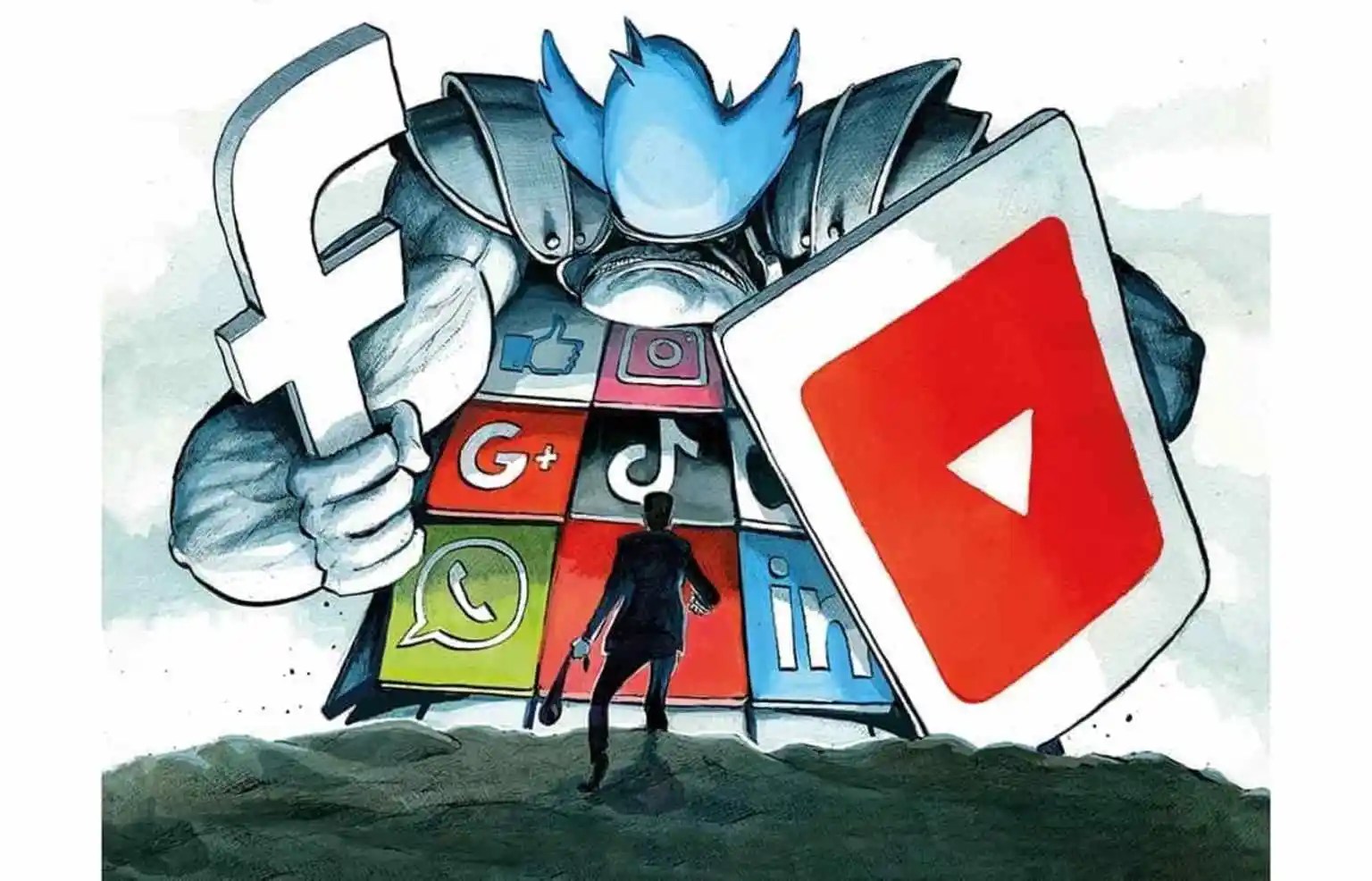

This raises the vital issue of the loss of tech sovereignty where the UK and EU authorities have been overwhelmed and effectively neutered. The dominance of Silicon Valley companies in search (Google), social media (Facebook), entertainment (Netflix) and e-commerce (Amazon) has become a pressing issue, fostering a belated debate on how we could have allowed it to happen.

As for Arm, in 2023 SoftBank decided that it should relist the business on the stock market but anchored to a US exchange. The British Prime Minister, Rishi Sunak, joined numerous discussions to bring Arm back to Britain, and begged SoftBank to offer a secondary listing of Arm shares in the UK. This too was denied. Victoria Scholar, the head of investment at Interactive Investor, told the Guardian: ‘Arm’s abandonment of London is another kick in the teeth for the Square Mile’s attractiveness among international investors as a go-to destination for technology giants.’

The headline figures speak for themselves. The UK economy grew sluggishly in the years following the great recession of 2008 but, in the same period, the UK earnings of America’s biggest tech firms skyrocketed, as shown here:

Today, Amazon collects more than 30 per cent of all UK online spending, and is growing steadily. That is profit-producing income that could have remained in the UK but that will now ultimately return to, and be controlled from, Amazon’s headquarters in Seattle.

Meta and Google receive two-thirds of all the UK’s expenditure on search and display advertising. The profit from that could have travelled to UK broadcasters and local newspapers, but it now ends up in California.

The profits made by US firms in the UK may help deliver value to consumers. But they have also built up market power that small domestic businesses do not have, forcing them to become US business rule-takers in their own economy. And the position of UK domestic business is weakening.

For example, of the biggest US tech companies operating in the UK, most reap the benefits of ‘network effects’ in which as more users join a platform, the more useful the platform becomes, and the harder it is for customers to switch to a rival. Microsoft’s LinkedIn site and its Office products are all more useful because others also use them. In the aftermath of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, in which Facebook user data ended up in the hands of an unscrupulous political consultancy, one reporter put it like this: ‘Facebook knows that as long as your 2 billion friends are online, you’re probably not going anywhere.’ Similar network effects explain why Threads found it impossible to displace Twitter/X in mid-2023. Users build up a platform’s power because innovations and revenue streams can be rolled out internationally to billions of people at once.

In media streaming, scale is critical. For example, Netflix boasted that it invested $17 billion in content in 2023 and was instantly able to distribute that content to 238 million subscribers in more than 150 countries. In contrast, when the production companies that feed UK broadcasters seek international deals for their shows, each one must be individually negotiated.

Scaled businesses using the network effect are well placed to diversify, too. In addition to its own distribution business, Amazon has expanded into streaming services, home entertainment and, of course, broader tech services. As if to demonstrate the power of scale, Amazon has created a platform through which many UK-based suppliers can sell. It has become so large that 60 per cent of Amazon sales are now made through its ‘Amazon Marketplace’. Amazon takes a margin on all these sales, builds its brand, dictates service quality and refers all problems back to the suppliers. The major advantage to Amazon is that for these Marketplace sales it does not need to hold any stock: it has become for many UK businesses the toll bridge which they must cross. Jeff Bezos’s vision that his platform should become the ‘everything store’ offering limitless selection and seductive convenience at disruptively low prices is now entrenched as the dominant force in UK retail commerce.

Britain’s consumers, workers and businesses are learning exactly what it means to be a twenty-first century vassal

Amazon Web Services (AWS) began as an attempt by Amazon to control its own web hosting, creating a system that could handle the growing data storage and traffic to its site. By 2002, Jeff Bezos had dispatched a team of data scientists to South Africa to develop a product for others to use, now known as ‘the cloud’. It took just two years to launch but it grew fast without dramatically increasing overheads.

‘This has to scale to infinity,’ Mr Bezos instructed staff, ‘with no planned downtime. Infinity!’ Today, AWS is worth at least $500 billion to its parent company. Most of the UK government’s websites and data are on AWS, which hosts everything from websites to streamed video. Even Britain’s most popular porn site, Pornhub, of Canada, with 2 billion UK visits annually (yes, billion), is hosted on AWS. Although Amazon does not have the UK market to itself, it does have about 40 per cent, and its competitors are all American: the other big players being Google Cloud Storage and Microsoft’s Azure.

Even for the smaller US tech firms, diversification and innovation are at the heart of their plans. Despite lack of profitability, Uber and Lyft have poured billions of dollars into research-and-development projects such as driverless cars.

Larger firms, meanwhile, push to buy up potential competitors and out-innovate their rivals to create unassailable market positions. In the past decade, Facebook decided to out-compete social media rival Snapchat by buying and rebuilding Instagram. Tesla, while selling electric vehicles more successfully than other car manufacturers, is also developing driverless systems. It is diversifying further, pledging to parlay its driverless-car research into developing a humanoid robot – called ‘Optimus’ or the ‘Tesla Bot’. Ultimately, these businesses hope to build what investor Warren Buffett calls ‘moats’ around themselves: a set of unique characteristics that ensure consumers are hooked and their behaviour is predictable and predictably advantageous for the company. Following Buffett’s investment in Apple, one of his colleagues described Apple’s moat: ‘Once you are fully invested in the Apple ecosystem and you’ve got your thousands of photographs up and in the cloud and you are used to the keystrokes and functionality and know where everything is, you become a sticky consumer.’

One of Amazon’s moats is its compelling sales offering, with an intuitive website and speedy delivery. Another is the ‘Kindle ecosystem’ for digital book sales, which is unrivalled. Uber offers special value and convenience through its app and dense network of vehicles on the road. Airbnb has an unmatched roster of landlords prepared to offer rooms, huts and homes on short leases. The sheer scale of Facebook’s popularity is a moat – which includes 73 per cent of all regular internet users in the UK – and the platforms owned by Facebook/Meta combine to reinforce it: Instagram, Messenger, WhatsApp and Facebook.

Each of these businesses builds momentum: surplus revenue is poured into R&D, and into diversification. The new products and services are themselves also scalable, and they bind customers more closely to the original brand, creating new customers for it. Quickly, this process repeats until the business’s position becomes entrenched, creating a de facto monopoly. At that point it can churn out profits. A virtuous cycle – but if your firm is on the outside, failing to scale and at the mercy of impatient investors, you might sell out instead. The quick return has mostly been the British way.

In 2010, the Bank of England’s chief economist warned of short-termism in the UK markets, and since then academic studies have provided more evidence that ‘systematic pressures exist in the UK context for the over-payment of dividends, leading to potential underinvestment’.

Consider the position of one of Britain’s biggest public technology companies: Aviva. At the start of 2024, the proportion of earnings paid out as dividends to shareholders was 280 per cent. In August 2023, Aviva’s half-yearly report boasted: ‘The consistency and strength of our performance supports the delivery of attractive outcomes for our shareholders.’

Compare the tone with that of Netflix in their 2017 annual report: ‘We are in no rush to push margins up too quickly,’ it told shareholders, ‘as we want to ensure we are investing aggressively enough to continue to lead internet TV around the world.’ Amazon has a similar vision for a strategy of domination: in his report for the first quarter of 2020, Bezos said: ‘If you are a shareowner in Amazon, you may want to take a seat, because we’re not thinking small.’ Amazon may have paid for its founder’s trip to space, but it has never paid a dividend and is not thinking of doing so any time soon.

In Britain it is said that dividends keep managers ‘honest’. But in the tech economy, the demand for dividends helps keep UK businesses small – and potential US competitors want them to stay that way. And if British businesses are small, they are discovering that they feel it when dealing with scaled, diversified and ‘moated’ US corporations as they have little power and little choice about what they pay, how they pay it or what information they must disclose to do business.

For Hermann Hauser, all this comes down to three questions, as paraphrased in an article for Forbes: ‘Do we control the critical technology in our own country? Do we have access to the technology from multiple independent countries? Do we have long-term, guaranteed, unfettered and secure access to the technology from a monopoly or oligopoly supplier from a single country?’ Hauser elaborated as follows: ‘If the answer to the above three questions is no, you have to make changes. There is a danger of becoming a new vassal state to these tech giants. It’s the danger of a new kind of colonialism, which is not enforced by military might but by economic dependence.’

Britain’s consumers, workers and businesses are learning exactly what it means to be a twenty-first-century vassal and to be plundered by a more powerful nation. They are learning the advantages of scale in technology, but also how the tech giants and the US platforms have become deeply embedded in the UK. And how US companies take a slice out of almost every transaction.

Freddy Gray speaks to Angus Hanton & Social Democratic Party leader William Clouston for the Americano podcast:

©Angus Hanton from Vassal State: How America Runs Britain (Swift Press, £25 hardback).