Reuters

ReutersLabour declared after the election that “Britain is back” on the world stage after years of Conservative retreat.

But when it comes to China, the government is tiptoeing nervously in the wings.

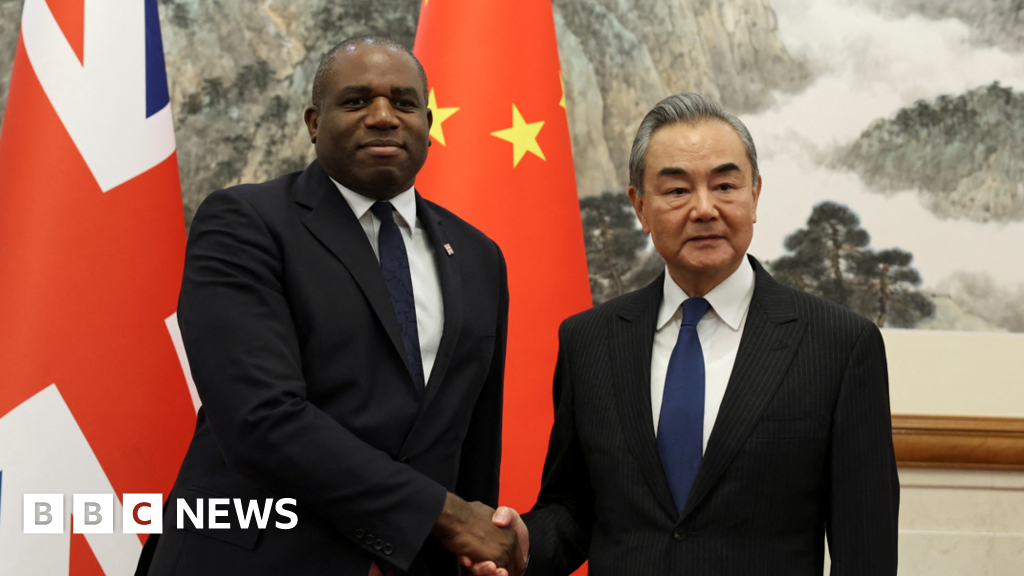

David Lammy’s trip to China is rare – he is only the second foreign secretary to visit in six years.

He held talks in Beijing with his powerful counterpart, Wang Yi, and Vice Premier Ding Xuexiang, before heading to Shanghai to meet British business leaders on Saturday.

You might think the Foreign Office would want to make a big thing of it, to emphasise the importance of the diplomatic repair job the foreign secretary is bent on.

But instead, the trip is taking place sotto voce.

There is little media access to Mr Lammy. There are no announcements about a new trade agreement, or cooperation on policy.

Whitehall sources tell me this in part the fault of Downing Street which, they say, is increasingly gripped by caution after a febrile few weeks.

No10 officials want to avoid political rows ahead of the Budget later this month. They do not want Labour and Conservative MPs to unite in accusing the government of putting economic gain ahead of human rights and international law.

There is a strong cross-party caucus in Westminster that is China-sceptic; seven MPs and peers remain officially sanctioned by Beijing as a result.

They are already accusing Mr Lammy of backtracking on pre-election promises to push the international courts to declare China’s treatment of the Uighur minority as genocide.

Perhaps the chief reason for the low-key nature of Mr Lammy’s visit is that Labour is still working out its policy towards China.

It is conducting what it calls a cross-Whitehall “audit” of Britain’s relationship with the country, which is not due to complete until next year. It is then that Chancellor Rachel Reeves, and perhaps even Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer, may visit China.

For now, the government has a holding position which it sums up in three words: “challenge, compete, cooperate”.

It says it will challenge China on human rights abuses and its support for Russia in Ukraine. It will compete with China over trade. And it will cooperate with China over shared interests, such as global health and climate change.

If this sounds familiar, that is because other western powers use similar language. And the previous Conservative government’s policy was to “protect, align and engage”.

However, both parties have found it difficult to work out where precisely to draw the line.

Does “compete” involve banning Chinese electric vehicles from the UK’s automotive market?

Does “challenge” mean restricting lucrative Chinese students from attending cash-strapped UK universities?

Does “cooperate” involve sharing private medical research to help prevent a future pandemic?

The head of MI5, Ken McCallum, spoke only last week of “a threat that manifests at scale” from China, targeting Britain’s information and democracy.

Mr Lammy’s more prosaic aim on this visit is simply to re-establish some kind of working relationship with Beijing.

Under the Conservatives, UK-China relations blew hot and cold, between the diplomatic warmth of the so-called “golden era” to the hawkish aggression of more recent Conservative leaders.

Last year, then-Prime Minister Rishi Sunak called China the “greatest threat” to Britain’s economy; then-Foreign Secretary James Cleverly visited Beijing calling for re-engagement; his successor Lord Cameron resolutely ignored the country.

Mr Lammy says he wants to re-establish what he calls a more consistent and pragmatic relationship.

During his talks with Mr Wang, he said he was “struck by the scope for mutually beneficial cooperation on the climate, on energy and nature, of the science and tech, on trade and investment, on health and development.”

He said Beijing and London should “find pragmatic solutions to complex challenges”.

China appears up for that. Mr Wang said China-UK relations were “standing at a new starting point” and spoke of “our boosted confidence in bilateral cooperation”.

He even referred by name to Mr Lammy’s foreign policy slogan – “progressive realism” – which Mr Wang said, “has positive significance”.

So far, so conciliatory.

Of course, Mr Lammy said both countries had “different perspectives” on some issues.

In a statement after the talks, the Foreign Office said he raised concerns about China’s military support for Russia in Ukraine, and how that was damaging China’s relationships in Europe.

The department also said he raised China’s treatment of the Uighurs in the Xinjiang region, “serious concerns” over the implementation of new national security laws in Hong Kong, and called for the release of the British media tycoon Jimmy Lai, who has been arbitrarily detained there.

But it insisted the meeting was “constructive across the full breadth of the bilateral relationship” and both sides committed to “regular discussions” at ministerial level.

For that ultimately is what this trip is all about: re-establishing links with the Chinese government.

The government’s priority is economic growth, and that is hard without a working relationship with its fourth largest trading partner.

But when it comes to China, it still remains unclear where Labour will draw the line between challenging, competing and cooperating.